Introduction

In the past weeks I enjoyed working on reversing a piece of software (don't ask me the name), to study how serial numbers are validated. The story the user has to follow is pretty common: download the trial, pay, get the serial number, use it in the annoying nag screen to get the fully functional version of the software.

Since my purpose is to not damage the company developing the software, I will not mention the name of the software, nor I will publish the final key generator in binary form, nor its source code. My goal is instead to study a real case of serial number validation, and to highlight its weaknesses.

In this post we are going to take a look at the steps I followed to reverse the serial validation process and to make a key generator using KLEE symbolic virtual machine. We are not going to follow all the details on the reversing part, since you cannot reproduce them on your own. We will concentrate our thoughts on the key-generator itself: that is the most interesting part.

Getting acquainted

The software is an x86 executable, with no anti-debugging, nor anti-reversing techniques. When started it presents a nag screen asking for a registration composed by: customer number, serial number and a mail address. This is fairly common in software.

Tools of the trade

First steps in the reversing are devoted to find all the interesting functions to analyze. To do this I used IDA Pro with Hex-Rays decompiler, and the WinDbg debugger. For the last part I used KLEE symbolic virtual machine under Linux, gcc compiler and some bash scripting. The actual key generator was a simple WPF application.

Let me skip the first part, since it is not very interesting. You can find many other articles on the web that can guide you through basic reversing techniques with IDA Pro. I only kept in mind some simple rules, while going forward:

- always rename functions that uses interesting data, even if you don't know precisely what they do. A name like

license_validation_unknown_8is always better than a default likesub_46fa39; - similarly, rename data whenever you find it interesting;

- change data types when you are sure they are wrong: use structs and arrays in case of aggregates;

- follow cross references of data and functions to expand your collection;

- validate your beliefs with the debugger if possible. For example, if you think a variable contains the serial, break with the debugger and see if it is the case.

Big picture

When I collected the most interesting functions, I tried to understand the high level flow and the simpler functions. Here are the main variables and types used in the validation process. As a note for the reader: most of them have been purged of uninteresting details, for the sake of simplicity.

enum {

ERROR,

STANDARD,

PRO

} license_type = ERROR;

Here we have a global variable providing the type of the license, used to enable and disable features of the application.

enum result_t {

INVALID,

VALID,

VALID_IF_LAST_VERSION

};

This is a convenient enum used as a result for the validation. INVALID and VALID values are pretty self-explanatory. VALID_IF_LAST_VERSION tells that this registration is valid only if the current software version is the last available. The reasons for this strange possibility will be clear shortly.

#define HEADER_SIZE 8192

struct {

int header[HEADER_SIZE];

int data[1000000];

} mail_digest_table;

This is a data structure, containing digests of mail addresses of known registered users. This is a pretty big file embedded in the executable itself. During startup, a resource is extracted in a temporary file and its content copied into this struct. Each element of the header vector is an offset pointing inside the data vector.

Here we have a pseudo-C code for the registration check, that uses data types and variables explained above:

enum result_t check_registration(int serial, int customer_num, const char* mail) {

// validate serial number

license_type = get_license_type(serial);

if (license_type == ERROR)

return INVALID;

// validate customer number

int expected_customer = compute_customer_number(serial, mail);

if (expected_customer != customer_num)

return INVALID;

// validate w.r.t. known registrations

int index = get_index_in_mail_table(serial);

if (index > HEADER_SIZE)

return VALID_IF_LAST_VERSION;

int mail_digest = compute_mail_digest(mail);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; ++i) {

if (mail_digest_table[index + i] == mail_digest)

return VALID;

}

return INVALID;

}

The validation is divided in three main parts:

- serial number must be valid by itself;

- serial number, combined with mail address has to correspond to the actual customer number;

- there has to be a correspondence between serial number and mail address, stored in a static table in the binary.

The last point is a little bit unusual. Let me restate it in this way: whenever a customer buys the software, the customer table gets updated with its data and become available in the next version of the software (because it is embedded in the binary and not downloaded trough the internet). This explains the VALID_IF_LAST_VERSION check: if you buy the software today, the current version does not contain your data. You are still allowed to get a "pro" version until a new version is released. In that moment you are forced to update to that new version, so the software can verify your registration with the updated table. Here is a pseudo-code of that check:

switch (check_registration(serial, customer, mail)) {

case VALID:

// the registration is OK! activate functionalities

activate_pro_functionality();

break;

case VALID_IF_LAST_VERSION:

{

// check if the current version is the last, by

// using the internet.

int current_version = get_current_version();

int last_version = get_last_version();

if (current_version == last_version)

// OK for now: a new version is not available

activate_pro_functionality();

else

// else, force the user to download the new version

// before proceed

ask_download();

}

break;

case INVALID:

// registration is not valid

handle_invalid_registration();

break;

}

The version check is done by making an HTTP request to a specific page that returns a page having only the last version number of the software. Don't ask me why the protection is not completely server side but involves static tables, version checks and things like that. I don't know!

Anyway, this is the big picture of the registration validation functions, and this is pretty boring. Let's move on to the interesting part. You may notice that I provided code for the main procedure, but not for the helper functions like get_license_type, compute_customer_number, and so on. This is because I did not have to reverse them. They contain a lot of arithmetical and logical operations on registration data, and they are very difficult to understand. The good news is that we do not have to understand them, we need only to reverse them!

Symbolic execution

Symbolic execution is a way to execute programs using symbolic variables instead of concrete values. A symbolic variable is used whenever a value can be controlled by user input (this can be done by hand or determined by using taint analysis), and could be a file, standard input, a network stream, etc. Symbolic execution translates the program's semantics into a logical formula. Each instruction cause that formula to be updated. By solving a formula for one path, we get concrete values for the variables. If those values are used in the program, the execution reaches that program point. Dynamic Symbolic Execution (DSE) builds the logical formula at runtime, step-by-step, following one path at a time. When a branch of the program is found during the execution, the engine transforms the condition into arithmetic operations. It then chooses the T (true) or F (false) branch and updates the formula with this new constraint (or its negation). At the end of a path, the engine can backtrack and select another path to execute. For example:

int v1 = SymVar_1, v2 = SymVar_2; // symbolic variables

if (v1 > 0)

v2 = 0;

if (v2 == 0 && v1 <= 0)

error();

We want to check if error is reachable, by using symbolic variables SymVar_1 and SymVar_2, assigned to the program's variables v1 and v2. In line 2 we have the condition v1 > 0 and so, the symbolic engine adds a constraint SymVar_1 > 0 for the true branch or conversely SymVar_1 <= 0 for the false branch. It then continues the execution trying with the first constraint. Whenever a new path condition is reached, new constraints are added to the symbolic state, until that condition is no more satisfiable. In that case, the engine backtracks and replaces some constraints with their negation, in order to reach other code paths. The execution engine tries to cover all code paths, by solving those constraints and their negations. For each portion of the code reached, the symbolic engine outputs a test case covering that part of the program, providing concrete values for the input variables. In the particular example given, the engine continues the execution, and finds the condition v2 == 0 && v1 <= 0 at line 4. The path formula becomes so: SymVar_1 > 0 && (SymVar_2 == 0 && SymVar_1 <= 0), that is not satisfiable. The symbolic engine provides then values for the variables that satisfies the previous formula (SymVar_1 > 0). For example SymVar_1 = 1 and some random value for SymVar_2. The engine then backtrack to the previous branch and uses the negation of the constraint, that is SymVar_1 <= 0. It then adds the negation of the current constraint to cover the false branch, obtaining SymVar_1 <= 0 && (SymVar_2 != 0 || SymVar_1 > 0). This is satisfiable with SymVar_1 = -1 and SymVar_2 = 0. This concludes the analysis of the program paths, and our symbolic execution engine can output the following test cases:

v1 = 1;v1 = -1,v2 = 0.

Those test cases are enough to cover all the paths of the program.

This approach is useful for testing because it helps generating test cases. It is often effective, and it does not waste computational power of your brain. You know... tests are very difficult to do effectively, and brain power is such a scarce resource!

I don't want to elaborate too much on this topic because it is way too big to fit in this post. Moreover, we are not going to use symbolic execution engines for testing purpose. This is just because we don't like to use things in the way they are intended :)

However, I will point you to some good references in the last section. Here I can list a series of common strengths and weaknesses of symbolic execution, just to give you a little bit of background:

Strengths:

- when a test case fails, the program is proven to be incorrect;

- automatic test cases catch errors that often are overlooked in manual written test cases (this is from KLEE paper);

- when it works it's cool :) (and this is from Jérémy);

Weaknesses:

- when no tests fail we are not sure everything is correct, because no proof of correctness is given; static analysis can do that when it works (and often it does not!);

- covering all the paths is not enough, because a variable can hold different values in one path and only some of them cause a bug;

- complete coverage for non trivial programs is often impossible, due to path explosion or constraint solver timeout;

- scaling is difficult, and execution time of the engine can suffer;

- undefined behavior of CPU could lead to unexpected results;

- ... and maybe there are a lot more remarks to add.

KLEE

KLEE is a great example of a symbolic execution engine. It operates on LLVM byte code, and it is used for software verification purposes. KLEE is capable to automatically generate test cases achieving high code coverage. KLEE is also able to find memory errors such as out of bound array accesses and many other common errors. To do that, it needs an LLVM byte code version of the program, symbolic variables and (optionally) assertions. I have also prepared a Docker image with clang and klee already configured and ready to use. So, you have no excuses to not try it out! Take this example function:

#define FALSE 0

#define TRUE 1

typedef int BOOL;

BOOL check_arg(int a) {

if (a > 10)

return FALSE;

else if (a <= 10)

return TRUE;

return FALSE; // not reachable

}

This is actually a silly example, I know, but let's pretend to verify this function with this main:

#include <assert.h>

#include <klee/klee.h>

int main() {

int input;

klee_make_symbolic(&input, sizeof(int), "input");

return check_arg(input);

}

In main we have a symbolic variable used as input for the function to be tested. We can also modify it to include an assertion:

BOOL check_arg(int a) {

if (a > 10)

return FALSE;

else if (a <= 10)

return TRUE;

klee_assert(FALSE);

return FALSE; // not reachable

}

We can now use clang to compile the program to the LLVM byte code and run the test generation with the klee command:

clang -emit-llvm -g -o test.ll -c test.c

klee test.ll

We get this output:

KLEE: output directory is "/work/klee-out-0"

KLEE: done: total instructions = 26

KLEE: done: completed paths = 2

KLEE: done: generated tests = 2

KLEE will generate test cases for the input variable, trying to cover all the possible execution paths and to make the provided assertions to fail (if any given). In this case we have two execution paths and two generated test cases, covering them. Test cases are in the output directory (in this case /work/klee-out-0). The soft link klee-last is also provided for convenience, pointing to the last output directory. Inside that directory a bunch of files were created, including the two test cases named test000001.ktest and test000002.ktest. These are binary files, which can be examined with the ktest-tool utility. Let's try it:

$ ktest-tool --write-ints klee-last/test000001.ktest

ktest file : 'klee-last/test000001.ktest'

args : ['test.ll']

num objects: 1

object 0: name: 'input'

object 0: size: 4

object 0: data: 2147483647

And the second one:

$ ktest-tool --write-ints klee-last/test000002.ktest

...

object 0: data: 0

In these test files, KLEE reports the command line arguments, the symbolic objects along with their size and the value provided for the test. To cover the whole program, we need input variable to get a value greater than 10 and one below or equal. You can see that this is the case: in the first test case the value 2147483647 is used, covering the first branch, while 0 is provided for the second, covering the other branch.

So far, so good. But what if we change the function in this way?

BOOL check_arg(int a) {

if (a > 10)

return FALSE;

else if (a < 10) // instead of <=

return TRUE;

klee_assert(FALSE);

return FALSE; // now reachable

}

We get this output:

$ klee test.ll

KLEE: output directory is "/work/klee-out-2"

KLEE: ERROR: /work/test.c:9: ASSERTION FAIL: 0

KLEE: NOTE: now ignoring this error at this location

KLEE: done: total instructions = 27

KLEE: done: completed paths = 3

KLEE: done: generated tests = 3

And this is the klee-last directory contents:

$ ls klee-last/

assembly.ll run.istats test000002.assert.err test000003.ktest

info run.stats test000002.ktest warnings.txt

messages.txt test000001.ktest test000002.pc

Note the test000002.assert.err file. If we examine its corresponding test file, we have:

$ ktest-tool --write-ints klee-last/test000002.ktest

ktest file : 'klee-last/test000002.ktest'

...

object 0: data: 10

As we had expected, the assertion fails when input value is 10. So, as we now have three execution paths, we also have three test cases, and the whole program gets covered. KLEE provides also the possibility to replay the tests with the real program, but we are not interested in it now. You can see a usage example in this KLEE tutorial.

KLEE's abilities to find execution paths of an application are very good. According to the OSDI 2008 paper, KLEE has been successfully used to test all 89 stand-alone programs in GNU COREUTILS and the equivalent busybox port, finding previously undiscovered bugs, errors and inconsistencies. The achieved code coverage were more than 90% per tool. Pretty awesome!

But, you may ask: The question is, who cares?. You will see it in a moment.

KLEE to reverse a function

As we have a powerful tool to find execution paths, we can use it to find the path we are interested in. As showed by the nice symbolic maze post of Feliam, we can use KLEE to solve a maze. The idea is simple but very powerful: flag the portion of code you interested in with a klee_assert(0) call, causing KLEE to highlight the test case able to reach that point. In the maze example, this is as simple as changing a read call with a klee_make_symbolic and the prinft("You win!\n") with the already mentioned klee_assert(0). Test cases triggering this assertion are the one solving the maze!

For a concrete example, let's suppose we have this function:

int magic_computation(int input) {

for (int i = 0; i < 32; ++i)

input ^= 1 << i;

return input;

}

And we want to know for what input we get the output 253. A main that tests this could be:

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

int input = atoi(argv[1]);

int output = magic_computation(input);

if (output == 253)

printf("You win!\n");

else

printf("You lose\n");

return 0;

}

KLEE can resolve this problem for us, if we provide symbolic inputs and actually an assert to trigger:

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

int input, result;

klee_make_symbolic(&input, sizeof(int), "input");

result = magic_computation(input);

if (result == 253)

klee_assert(0);

return 0;

}

Run KLEE and print the result:

$ clang -emit-llvm -g -o magic.ll -c magic.c

$ klee magic.ll

$ ktest-tool --write-ints klee-last/test000001.ktest

ktest file : 'klee-last/test000001.ktest'

args : ['magic.ll']

num objects: 1

object 0: name: 'input'

object 0: size: 4

object 0: data: -254

The answer is -254. Let's test it:

$ gcc magic.c

$ ./a.out -254

You win!

Yes!

KLEE, libc and command line arguments

Not all the functions are so simple. At least we could have calls to the C standard library such as strlen, atoi, and such. We cannot link our test code with the system available C library, as it is not inspectable by KLEE. For example:

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

int input = atoi(argv[1]);

return input;

}

If we run it with KLEE we get this error:

$ clang -emit-llvm -g -o atoi.ll -c atoi.c

$ klee atoi.ll

KLEE: output directory is "/work/klee-out-4"

KLEE: WARNING: undefined reference to function: atoi

KLEE: WARNING ONCE: calling external: atoi(0)

KLEE: ERROR: /work/atoi.c:5: failed external call: atoi

KLEE: NOTE: now ignoring this error at this location

...

To fix this we can use the KLEE uClibc and POSIX runtime. Taken from the help:

"If we were running a normal native application, it would have been linked with the C library, but in this case KLEE is running the LLVM bitcode file directly. In order for KLEE to work effectively, it needs to have definitions for all the external functions the program may call. Similarly, a native application would be running on top of an operating system that provides lower level facilities like write(), which the C library uses in its implementation. As before, KLEE needs definitions for these functions in order to fully understand the program. We provide a POSIX runtime which is designed to work with KLEE and the uClibc library to provide the majority of operating system facilities used by command line applications".

Let's try to use these facilities to test our atoi function:

$ klee --optimize --libc=uclibc --posix-runtime atoi.ll --sym-args 0 1 3

KLEE: NOTE: Using klee-uclibc : /usr/local/lib/klee/runtime/klee-uclibc.bca

KLEE: NOTE: Using model: /usr/local/lib/klee/runtime/libkleeRuntimePOSIX.bca

KLEE: output directory is "/work/klee-out-5"

KLEE: WARNING ONCE: calling external: syscall(16, 0, 21505, 70495424)

KLEE: ERROR: /tmp/klee-uclibc/libc/stdlib/stdlib.c:526: memory error: out of bound pointer

KLEE: NOTE: now ignoring this error at this location

KLEE: done: total instructions = 5756

KLEE: done: completed paths = 68

KLEE: done: generated tests = 68

And KLEE founds the possible out of bound access in our program. Because you know, our program is bugged :) Before to jump and fix our code, let me briefly explain what these new flags did:

--optimize: this is for dead code elimination. It is actually a good idea to use this flag when working with non-trivial applications, since it speeds things up;--libc=uclibcand--posix-runtime: these are the aforementioned options for uClibc and POSIX runtime;--sym-args 0 1 3: this flag tells KLEE to run the program with minimum 0 and maximum 1 argument of length 3, and make the arguments symbolic.

Note that adding atoi function to our code, adds 68 execution paths to the program. Using many libc functions in our code adds complexity, so we have to use them carefully when we want to reverse complex functions.

Let now make the program safe by adding a check to the command line argument length. Let's also add an assertion, because it is fun :)

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <assert.h>

#include <klee/klee.h>

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

int result = argc > 1 ? atoi(argv[1]) : 0;

if (result == 42)

klee_assert(0);

return result;

}

We could also have written klee_assert(result != 42), and get the same result. No matter what solution we adopt, now we have to run KLEE as before:

$ clang -emit-llvm -g -o atoi2.ll -c atoi2.c

$ klee --optimize --libc=uclibc --posix-runtime atoi2.ll --sym-args 0 1 3

KLEE: NOTE: Using klee-uclibc : /usr/local/lib/klee/runtime/klee-uclibc.bca

KLEE: NOTE: Using model: /usr/local/lib/klee/runtime/libkleeRuntimePOSIX.bca

KLEE: output directory is "/work/klee-out-6"

KLEE: WARNING ONCE: calling external: syscall(16, 0, 21505, 53243904)

KLEE: ERROR: /work/atoi2.c:8: ASSERTION FAIL: 0

KLEE: NOTE: now ignoring this error at this location

KLEE: done: total instructions = 5962

KLEE: done: completed paths = 73

KLEE: done: generated tests = 69

Here we go! We have fixed our bug. KLEE is also able to find an input to make the assertion fail:

$ ls klee-last/ | grep err

test000016.assert.err

$ ktest-tool klee-last/test000016.ktest

ktest file : 'klee-last/test000016.ktest'

args : ['atoi.ll', '--sym-args', '0', '1', '3']

num objects: 3

...

object 1: name: 'arg0'

object 1: size: 4

object 1: data: '+42\x00'

...

And the answer is the string "+42"... as we know.

There are many other KLEE options and functionalities, but let's move on and try to solve our original problem. Interested readers can find a good tutorial, for example, in How to Use KLEE to Test GNU Coreutils.

KLEE keygen

Now that we know basic KLEE commands, we can try to apply them to our particular case. We have understood some of the validation algorithm, but we don't know the computation details. They are just a mess of arithmetical and logical operations that we are tired to analyze.

Here is our plan:

- we need at least a valid customer number, a serial number and a mail address;

- more ambitiously we want a list of them, to make a key generator.

This is a possibility:

// copy and paste of all the registration code

enum {

ERROR,

STANDARD,

PRO

} license_type = ERROR;

// ...

enum result_t check_registration(int serial, int customer_num, const char* mail);

// ...

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

int serial, customer;

char mail[10];

enum result_t result;

klee_make_symbolic(&serial, sizeof(serial), "serial");

klee_make_symbolic(&customer, sizeof(customer), "customer");

klee_make_symbolic(&mail, sizeof(mail), "mail");

valid = check_registration(serial, customer, mail);

valid &= license_type == PRO;

klee_assert(!valid);

}

Super simple. Copy and paste everything, make the inputs symbolic and assert a certain result (negated, of course).

No! That's not so simple. This is actually the most difficult part of the game. First of all, what do we want to copy? We don't have the source code. In my case I used Hex-Rays decompiler, so maybe I have cheated. When you decompile, however, you don't get immediately a compilable C source code, since there could be dependencies between functions, global variables, and specific Hex-Rays types. For this latter problem I've prepared a ida_defs.h header, providing defines coming from IDA and from Windows headers.

But what to copy? The high level picture of the validation algorithm I have presented is an ideal one. The check_registration function is actually a big set of auxiliary functions and data, very tightened with other parts of the program. Even if we now know the most interesting functions, we need to know how much of the related code, is useful or not. We cannot throw everything in our key generator, since every function brings itself other related data and functions. In this way we will end up having the whole program in it. We need to minimize the code KLEE has to analyze, otherwise it will be too difficult to have its job done.

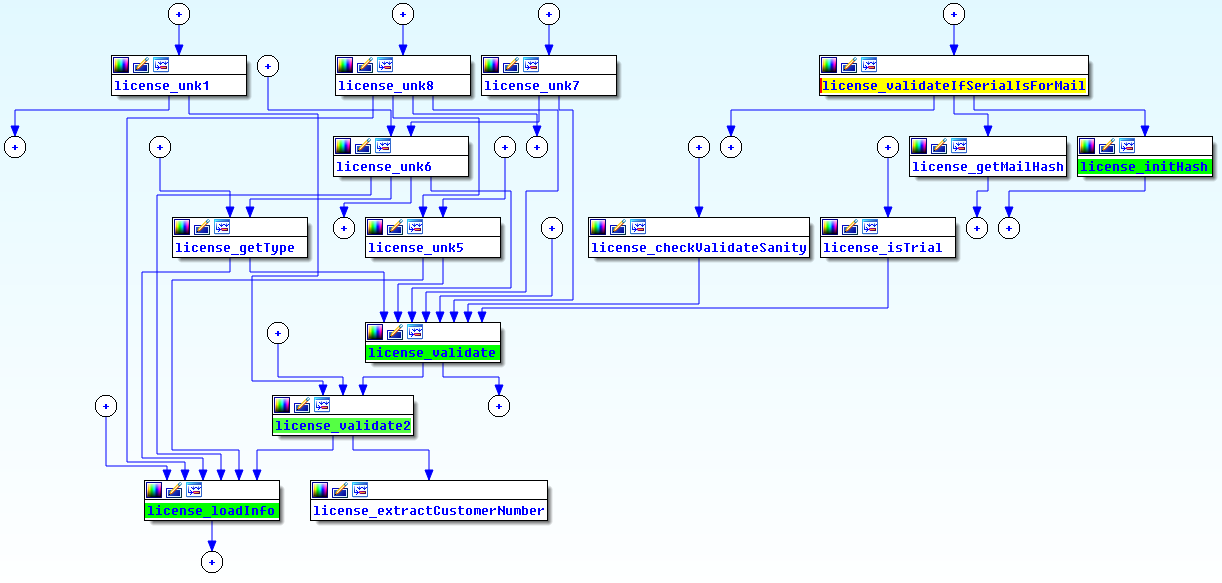

This is a picture of the high level workflow, as IDA proximity view proposes:

and this is the overview for a single node of this schema (precisely license_getType):

As you can imagine, the complete call graph becomes really big in the end.

In the cleanup process I have done, a big bunch of functions removed is the one extracting and loading the table of valid mail addresses. To do this I stepped with the debugger until the table was completely loaded and then dumped the memory of the process. Then I've used a nice "export to C array" functionality of HEX Workshop, to export the actual piece of memory of the mail table to actual code:

uint16_t hashHeader[8192] =

{

0x0, 0x28, 0x12, 0x24, 0x2d, 0x2b, 0x2e, 0x23, 0x2b, 0x26,

// ...

};

int16_t hashData[1000000] =

{

15306, 18899, 18957, -24162, 63045, -26834, -21, -39653, 271441, -5588,

// ...

};

But, cutting out code is not the only problem I've found in this step. External constraints must be carefully considered. For example the time function can be handled by KLEE itself. KLEE tries to generate useful values even from that function. This is good if we want to test bugs related to a strange current time, but in our case, since the code will be executed by the program at a particular time, we are only interested in the value provided at that time. We don't want KLEE traits this function as symbolic; we only want the right time value. To solve that problem, I have replaced all the calls to time to a my_time function, returning a fixed value, defined in the source code.

Another problem comes from the extraction of the functions from their outer context. Often code is written with implicit conventions in mind. These are not self-evident in the code because checks are avoided. A trivial example is the null terminator and valid ASCII characters in strings. KLEE does not assume those constraints, but the validation code does. This is because the GUI provides only valid strings. A less trivial example is that the mail address is always passed lowercase from the GUI to the lower level application logic. This is not self-evident if you do not follow every step from the user input to the actual computations with the data.

The solution to this latter problem is to provide those constraints to KLEE:

char mail[10];

char c;

klee_make_symbolic(mail, sizeof(mail), "mail");

for (i = 0; i < sizeof(mail) - 1; ++i) {

c = mail[i];

klee_assume( (c >= '0' & c <= '9') | (c >= 'a' & c <= 'z') | c == '\0' );

}

klee_assume(mail[sizeof(mail) - 1] == '\0');

Logical operators inside klee_assume function are bitwise and not logical (i.e. & and | instead of && and ||) because they are simpler, since they do not add the extra branches required by lazy operators.

Throw everything into KLEE

Having extracted all the needed functions and global data and solved all the issues with the code, we can now move on and run KLEE with our brand new test program:

$ clang -emit-llvm -g -o attempt1.ll -c attempt1.c

$ klee --optimize --libc=uclibc --posix-runtime attempt1.ll

And then wait for an answer.

And wait for another while.

Make some coffee, drink it, come back and watch the PC heating up.

Go out, walk around, come back, have a shower, and.... oh no! It's still running! OK, that's enough! Let's kill it.

Deconstruction approach

We have assumed too much from the tool. It's time to use the brain and ease its work a little bit.

Let's decompose the big picture of the registration check presented before piece by piece. We will try to solve it bit by bit, to reduce the solution space and so, the complexity.

Recall that the algorithm is composed by three main conditions:

- serial number must be valid by itself;

- serial number, combined with mail address have to correspond to the actual customer number;

- there has to be a correspondence between serial number and mail address, stored in a static table in the binary.

Can we split them in different KLEE runs?

Clearly the first one can be written as:

#include <assert.h>

#include <klee/klee.h>

// include all the functions extracted from the program

#include "extracted_code.c"

enum {

ERROR,

STANDARD,

PRO

} license_type = ERROR;

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

int serial, valid;

klee_make_symbolic(&serial, sizeof(serial), "serial");

license_type = get_license_type(serial);

valid = (license_type == PRO);

klee_assert(!valid);

}

And let's see if KLEE can work with this single function:

$ clang -emit-llvm -g -o serial_type.ll -c serial_type.c

$ klee --optimize --libc=uclibc --posix-runtime serial_type.ll

...

KLEE: ERROR: /work/symbolic/serial_type.c:17: ASSERTION FAIL: !valid

...

$ ls klee-last/ | grep err

test000019.assert.err

$ ktest-tool --write-ints klee-last/test000019.ktest

ktest file : 'klee-last/test000019.ktest'

args : ['serial_type.ll']

num objects: 2

object 0: name: 'model_version'

object 0: size: 4

object 0: data: 1

object 1: name: 'serial'

object 1: size: 4

object 1: data: 102690141

Yes! we now have a serial number that is considered PRO by our target application.

The third condition is less simple: we have a table in which are stored values matching mail addresses with serial numbers. The high level check is this:

int check(int serial, char* mail) {

int index = get_index_in_mail_table(serial);

if (index > HEADER_SIZE)

return VALID_IF_LAST_VERSION;

int mail_digest = compute_mail_digest(mail);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; ++i) {

if (mail_digest_table[index + i] == mail_digest)

return VALID;

}

return INVALID;

}

This piece of code imposes constraints on our mail address and serial number, but not on the customer number. We can rewrite the checks in two parts, the one checking the serial, and the one checking the mail address:

int check_serial(int serial, char* mail) {

int index = get_index_in_mail_table(serial);

int valid = index <= HEADER_SIZE;

}

int check_mail(char* mail, int index) {

int mail_digest = compute_mail_digest(mail);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; ++i) {

if (mail_digest_table[index + i] == mail_digest)

return 1;

}

return 0;

}

The check_mail function needs the index in the table as secondary input, so it is not completely independent from the other check function. However, check_mail can be incorporated by our successful test program used before:

// ...

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

int serial, valid, index;

klee_make_symbolic(&serial, sizeof(serial), "serial");

license_type = get_license_type(serial);

valid = (license_type == PRO);

// added just now

index = get_index_in_mail_table(serial);

valid &= index <= HEADER_SIZE;

klee_assert(!valid);

}

And if we run it, we get our revised serial number, that satisfies the additional constraint:

$ clang -emit-llvm -g -o serial.ll -c serial.c

$ klee --optimize --libc=uclibc --posix-runtime serial.ll

...

KLEE: ERROR: /work/symbolic/serial.c:21: ASSERTION FAIL: !valid

...

$ ls klee-last/ | grep err

test000032.assert.err

$ ktest-tool --write-ints klee-last/test000019.ktest

...

object 1: name: 'serial'

object 1: data: 120300641

...

For those who are wondering if get_index_in_mail_table could return a negative index, and so possibly crash the program I can answer that they are not alone. @0vercl0k asked me the same question, and unfortunately I have to answer a no. I tried, because I am a lazy ass, by changing the assertion above to klee_assert(index < 0), but it was not triggered by KLEE. I then manually checked the function's code and I saw a beautiful if (result < 0) result = 0. So, the answer is no! You have not found a vulnerability in the application :(

For the check_mail solution we have to provide the index of a serial, but wait... we have it! We have now a serial, so, computing the index of the table is simple as executing this:

int index = get_index_in_mail_table(serial);

Therefore, given a serial number, we can solve the mail address in this way:

// ...

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

int serial, valid, index;

char mail[10];

// mail is symbolic

klee_make_symbolic(mail, sizeof(mail), "mail");

for (i = 0; i < sizeof(mail) - 1; ++i)

{

c = mail[i];

klee_assume( (c >= '0' & c <= '9') | (c >= 'a' & c <= 'z') | c == '\0' );

}

klee_assume(mail[sizeof(mail) - 1] == '\0');

// get serial as external input

if (argc < 2)

return 1;

serial = atoi(argv[1]);

// compute index

index = get_index_in_mail_table(serial);

// check validity

valid = check_mail(mail, index);

klee_assert(!valid);

}

We only have to run KLEE with the additional serial argument, providing the computed one by the previous step.

$ clang -emit-llvm -g -o mail.ll -c mail.c

$ klee --optimize --libc=uclibc --posix-runtime mail.ll 120300641

...

KLEE: ERROR: /work/symbolic/mail.c:34: ASSERTION FAIL: !valid

...

$ ls klee-last/ | grep err

test000023.assert.err

$ ktest-tool klee-last/test000023.ktest

...

object 1: name: 'mail'

object 1: data: 'yrwt\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00'

...

OK, the mail found by KLEE is "yrwt". This is not a mail, of course, but in the code there is not a proper validation imposing the presence of '@' and '.' chars, so we are fine with it :)

The last piece of the puzzle we need is the customer number. Here is the check:

int expected_customer = compute_customer_number(serial, mail);

if (expected_customer != customer_num)

return INVALID;

This is simpler than before, since we already have a serial and a mail, so the only thing missing is a customer number matching those. We can compute it directly, even without symbolic execution:

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

if (argc < 3)

return 1;

int serial = atoi(argv[1]);

char* mail = argv[2];

int customer_number = compute_customer_number(serial, mail);

printf("%d\n", customer_number);

return 0;

}

Let's execute it:

$ gcc customer.c customer

$ ./customer 120300641 yrwt

1175211979

Yeah! And if we try those numbers and mail address onto the real program, we are now legit and registered users :)

Want more keys?

We have just found one key, and that's cool, but what about making a keygen? KLEE is deterministic, so if you run the same code over and over you will get always the same results. So, we are now stuck with this single serial.

To solve the problem we have to think about what variables we can move around to get different valid serial numbers to start with, and with them solve related mail addresses and compute a customer number.

We have to add constraints to the serial generation, so that every time we can run a slightly different version of the program and get a different serial number. The simplest thing to do is to constraint get_index_in_mail_table to return an index inside a proper subset of the range [0, HEADER_SIZE] used before. For example we can divide it in equal chunks of size 5 and run the whole thing for every chunk.

This is the modified version of the serial generation:

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

int serial, min_index, max_index, valid;

// get chunk bounds as external inputs

if (argc < 3)

return 1;

min_index= atoi(argv[1]);

max_index= atoi(argv[2]);

// check and assert

index = get_index_in_mail_table(serial);

valid = index >= min_index && index < max_index;

klee_assert(!valid);

return 0;

}

We now need a script that runs KLEE and collect the results for all those chunks. Here it is:

#!/bin/bash

MIN_INDEX=0

MAX_INDEX=8033

STEP=5

echo "Index;License;Mail;Customer"

for INDEX in $(seq $MIN_INDEX $STEP $MAX_INDEX); do

echo -n "$INDEX;"

CHUNK_MIN=$INDEX

CHUNK_MAX=$(( CHUNK_MIN + STEP ))

LICENSE=$(./solve.sh serial.ll $CHUNK_MIN $CHUNK_MAX)

if [ -z "$LICENSE" ]; then

echo ";;"

continue

fi

MAIL_ARRAY=$(./solve.sh mail.ll $LICENSE)

if [ -z "$MAIL_ARRAY" ]; then

echo ";;"

continue

fi

MAIL=$(sed 's/\\x00//g' <<< $MAIL_ARRAY | sed "s/'//g")

CUSTOMER=$(./customer $LICENSE $MAIL)

echo "$LICENSE;$MAIL;$CUSTOMER"

done

This script uses the solve.sh script, that does the actual work and prints the result of KLEE runs:

#!/bin/bash

# do work

klee $@ >/dev/null 2>&1

# print result

ASSERT_FILE=$(ls klee-last | grep .assert.err)

TEST_FILE=$(basename klee-last/$ASSERT_FILE .assert.err)

OUTPUT=$(ktest-tool --write-ints klee-last/$TEST_FILE.ktest | grep data)

RESULT=$(sed 's/.*:.*: //' <<< $OUTPUT)

echo $RESULT

# cleanup

rm -rf $(readlink -f klee-last)

rm -f klee-last

Here is the final run:

$ ./keygen_all.sh

Index;License;Mail;Customer

...

2400;;;

2405;115019227;4h79;1162863222

2410;112625605;7cxd;554797040

...

Note that not all the serial numbers are solvable, but we are OK with that. We now have a bunch of solved registrations. We can put them in some simple GUI that exposes to the user one of them randomly.

That's all folks.

Conclusion

This was a brief journey into the magic world of reversing and symbolic execution. We started with the dream to make a key generator for a real world application, and we've got a list of serial numbers to put in some nice GUI (maybe with some MIDI soundtrack playing in the background to make users crazy). But this was not our purpose. The path we followed is far more interesting than ruining programmer's life. So, just to recap, here are the main steps we followed to generate our serial numbers:

- reverse the skeleton of the serial number validation procedure, understanding data and the most important functions, using a debugger, IDA, and all the reversing tools we can access;

- collect the functions and produce a C version of them (this could be quite difficult, unless you have access to HEX-Rays decompiler or similar tool);

- mark some strategic variable as symbolic and mark some strategic code path with an assert;

- ask KLEE to provide us the values for symbolic variables that make the assert to fail, and so to reach that code path;

- since the last step provides us only a single serial number, add an external input to the symbolic program, using it as additional constraint, in order to get different values for symbolic variables reaching the assert.

The last point can be seen as quite obscure, I can admit that, but the idea is simple. Since KLEE's goal is to reach a path with some values for the symbolic variables, it is not interested in exploring all the possibilities for those values. We can force this exploration manually, by adding an additional constraint, and varying a parameter from run to run, and get (hopefully) different correct values for our serial number.

I would like to thank @0vercl0k, @jonathansalwan and @__x86 for their careful proofreading and good remarks!

I hope you found this topic interesting. In the case, here are some links that can be useful for you to deepen some of the arguments touched in this post:

- KLEE main site in which you can find documentation, examples and some news;

- My Docker image of KLEE that you can use as is if you want to avoid building KLEE from sources. It is an automated build (sources here) so you can use it safely;

- Tutorial on using KLEE onto GNU Coreutils is here if you want to learn to use better KLEE for testing purposes.

- The Feliam's article The Symbolic Maze! that gave me insights on how to use KLEE for reversing purposes;

- The paper Symbolic execution and program testing of James C. King gives you a nice intro on symbolic execution topic;

- Slides from this Harvard course are useful to visualize symbolic execution with nice figures and examples;

- Dynamic Binary Analysis and Instrumentation Covering a function using a DSE approach by Jonathan Salwan.

Source code, examples and scripts used to produce this blog post are published in this GitHub repo.

Cheers, @brt_device.